Mache: Out of Winter and into a Salad

You’ve probably noticed: it’s been a slow, slow spring. The one thing we can cultivate in this weather, aside from patience, are overwintered greens. New, crisp leaves - like mache or spinach - rising out of the snow, unfazed by the chaos of March, full of spring energy.

Mache - Valerianella locusta – also goes by corn salad, lamb’s lettuce, fetticus, feldsalat, nut lettuce, field salad, rapunzel, Doucette, rampon, rampien, betcke, milk grass, veticost, and white potherb. Its many names are telling of the many cultures it has found a place in and the diverse relationships it developed with humans. For livestock farmers, it’s just grass that cows munch on in the fields; for some chefs - a fleeting spring delicacy; for 17th century French peasants - an important winter vegetable. For northern gardeners, it is the too-often-overlooked answer to the fresh greens famine of late winter and early spring.

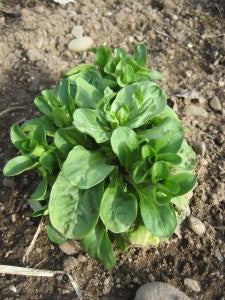

Mache has a nutty, mildly sweet taste and with leaves as delicate as lettuce. It grows in stout rosettes: 6 to 8 velvety leaves held up by the skinniest stems. It makes for a delicious and super healthy salad base. Like other plants that came into cultivation after first being foraged for in the wild, mache is packed with vitamins and minerals: like vitamins C, E and the Bs, beta-carotene, and omega-3 fatty acids. But, the biggest thing mache brings to our tables is not taste or nutrition, but its bravery when it comes to cold weather. It can withstand temperatures of 5 degrees Fahrenheit without protection and is the first to rise at the faintest sign of spring. With a little protectionLINK, it can be harvested all through the winter.

Mache was first brought to the dinner table from the wild, foraged by French peasants for centuries. After Jean-Baptiste de La Quintinie – King Louis XIV’s royal gardener – planted it in the king’s garden in the 17th century, Louis XIV took it upon himself to popularize this lovely salad green and it began to be cultivated throughout Europe. In North America, Mache has found a spokesperson in Todd Koons, the same person who introduced bagged salad greens to supermarkets around the country. Koons is on a mission to popularize Mache commercially, and currently grows 5 acres of the green per week in "the salad bowl of the world" - California's Salina's Valley. He’s hit a snag though, because no machinery currently exists that can cut a plant that’s so low to the ground. While Koons works on an “earth shaver,” home gardeners can continue to enjoy mache thanks to the simple joy of hand harvesting right into your salad bowl, bypassing plastic bags and a trip to the supermarket.

Growing Mache: Mache should be sown directly in full sun starting in late August through deep fall, and again in early spring as soon as the ground can be worked. Mache is not a picky plant: although it’s good to help it with water during dry spells and add a little fertilizer for green and lush leaves, it takes good care of itself. It is not a perennial, but behaves like one by self-sowing abundantly. Be sure to choose a somewhat permanent home for Mache in your garden, as it will eventually take over whatever space you offer it. To harvest, pick entire rosettes or individual leaves and keep in mind that flavor declines when Mache blooms. For a continual supply, sow in succession.