Get to know your garden! Here's the third post in our series of plant profiles. The topic? The ever popular cucumber--that crunchy, cool, refreshing summer treat that nearly everyone loves.

A little history from Alison: Cucumbers were developed by early farmers in India, soon spreading to Greece and Italy. Ancient Romans were particularly fond of cukes, using artificial methods to ensure the fruit's year-round availability--just like modern times! Romans would keep their cucumber plants mobile, wheeling them into the sun during the day, then later protecting them under frames or in special cucumber houses. North American cuke cultivation began in the 1500s. But by the late 1600s, fears of foodborne illnesses created a prejudice against fresh cucumbers (and all fresh vegetables). Soon cucumbers were deemed “fit only for consumption by cows,” earning it the nickname “cowcumber.” Despite this historic mis-guided debacle, cucumbers have enjoyed a vast popularity worldwide. There are generally two types of cucumbers: slicing cukes (long fruit used for raw eating) and pickling cukes (smaller fruit that is cured). More info and how-to after the pics.

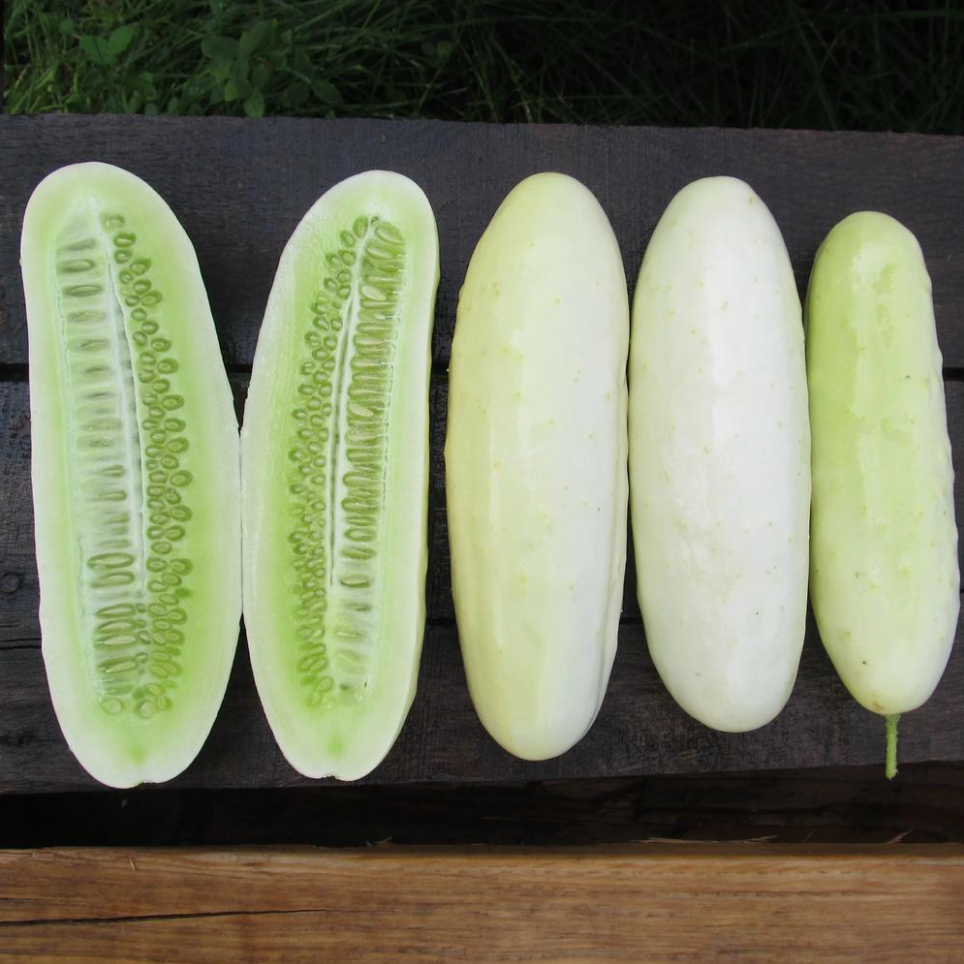

The Seed Library sells four types of cucumbers: Lemon Cucumbers are delicately flavored and not at all sour, despite their dead-ringer likeness to a certain neon-yellow citrus fruit. These cukes are round and yellow, great for raw eating or for pickling. Introduced by Cornell University in the '70s, Marketmore 76 is the standard for long, slicing cucumbers. The plant produces a great yield of cukes marked by their big size, dark-green skin, and mild flavor. Muncher Cucumber , available as an art pack and garden pack, are “burpless” varieties, which means it might actually induce less gas than other cukes. True or not, Muncher is mild and prolific, great pickled when young or eaten raw when mature. Double Yield cukes are a New York heirloom, excelling both as a pickler and a slicer. They are relatively thin-skinned, with a sweet, flavorful flesh.

More how-to from Doug: Think it's too late to grow cukes? Think again! Cucumbers are a relatively fast crop and can be sown successfully until about mid- to late-July in the Hudson Valley. In fact, to keep high-quality cukes on the table all season, you must re-sow several times during the season. Plants usually diminish after 3 weeks of harvest; having fresh young plants coming right along means another month of cucumber bliss. (Have a cold frame? You can sow even later and be harvesting fresh cukes into early November with a little protection.)

Cucumbers are greedy crops; give them plenty of fertility and keep them watered, and they will excel. Space plants about 18" apart in rows 36" apart. Alternately, sow a clump of 5 or 6 seeds in hills spaced 36" apart; thin to 3-4 plants per hill. Harvest as soon as cukes reach the edible stage, which varies by variety but is about 4-5 inches in length for most slicers. Stay on top of the harvest--as soon as you cease removing edible cukes, the fruit on the vine will swell, turn deep yellow, and mature. While this is great for seed-saving, it means the end of your cucumber harvest, as the plants will stop producing more young fruit once the fruit on the vine are maturing.

A common problem of cucumbers--especially in established gardens--is the cucumber beetle. Massive numbers of these striped, winged munchers appear in waves soon after the last frost of spring. Some years they will quickly disappear; some years they will return over and over. Keep an eye out. If cucumber beetles are a bother, quickly re-sow and cover plants with floating row cover--this will keep the bugs off and provide a bit of extra heat, which the cukes will enjoy. Even in a bad beetle season, you'll likely have at least a few plants that will survive the onslaught with little damage and will thrive.