Why garden? It's a question you might not have asked yourself, since most of us garden because we love it. Why wouldn't we garden? How could we not? But in a world where it's nearly always more convenient to skip the effort and head to the supermarket, it's worth pondering the virtues of working the soil. As growers of open-pollinated seed, one of our favorite advantages of the OP garden is the diversity. True, the grocery store is always going to have tomatoes, and they're all going to look smooth and shiny and they'll suffice for your salad. But how about growing not one but three tomato varieties, all with unique colors and flavors and uses? And a diverse garden isn't just more fun; by growing rare varieties—and saving their seeds—the home gardener can fight back against the loss of biodiversity in agriculture as crops are reduced to just a few monocultures.

Oh, and there's more: diversifying your garden can be beneficial to the plants you grow, giving them opportunities to support and rely on one another. A truly diverse garden isn't limited to any one type of crop; it incorporates vegetables, herbs, and flowers. But to truly experience the advantages takes planning, intention, and foresight. It can be helpful to think of it in two ways: a) how do I envision the season as a whole? and b) what seeds should I have growing together at any one time? Today, we'll explore just a few of the many ways you can start to think about your garden as a plentiful backyard ecosystem.

ENVISION YOUR SEASON

Planning may be the least fun part of gardening, but, as with cooking and comedy, timing is everything. And if you want a diverse garden, you'll have more plates spinning, so it's extra important to have a vision of what you want your garden to be. Ponder it, take notes, make sketches, and stick to them as much as you can. Think of the growing season in three time periods: early season, mid-season, and late season. The goal is to have varieties that grow, bloom, and fruit in each of those seasons. There are several types of diversity to consider here:

- Days to maturity: Look at each variety's "quick facts" and read the seed pack to find out how long they take to produce flowers or fruit. Consider those numbers in your planning, and use them to stagger or coordinate your crops.

- Think ahead: Winter squash may not be harvested until fall, but it should be planted shortly after your last frost, and started indoors even before that. Write down what you want to grow and how long it takes to grow it. If you need a handy guide to planting dates, you're in luck! Artist Cynthia Cliff of Seed Shaker fame designed a gorgeous early spring planting guide. Buy the full-size poster for your wall or greenhouse, or sign up for our newsletter at the bottom of the page and download it for free.

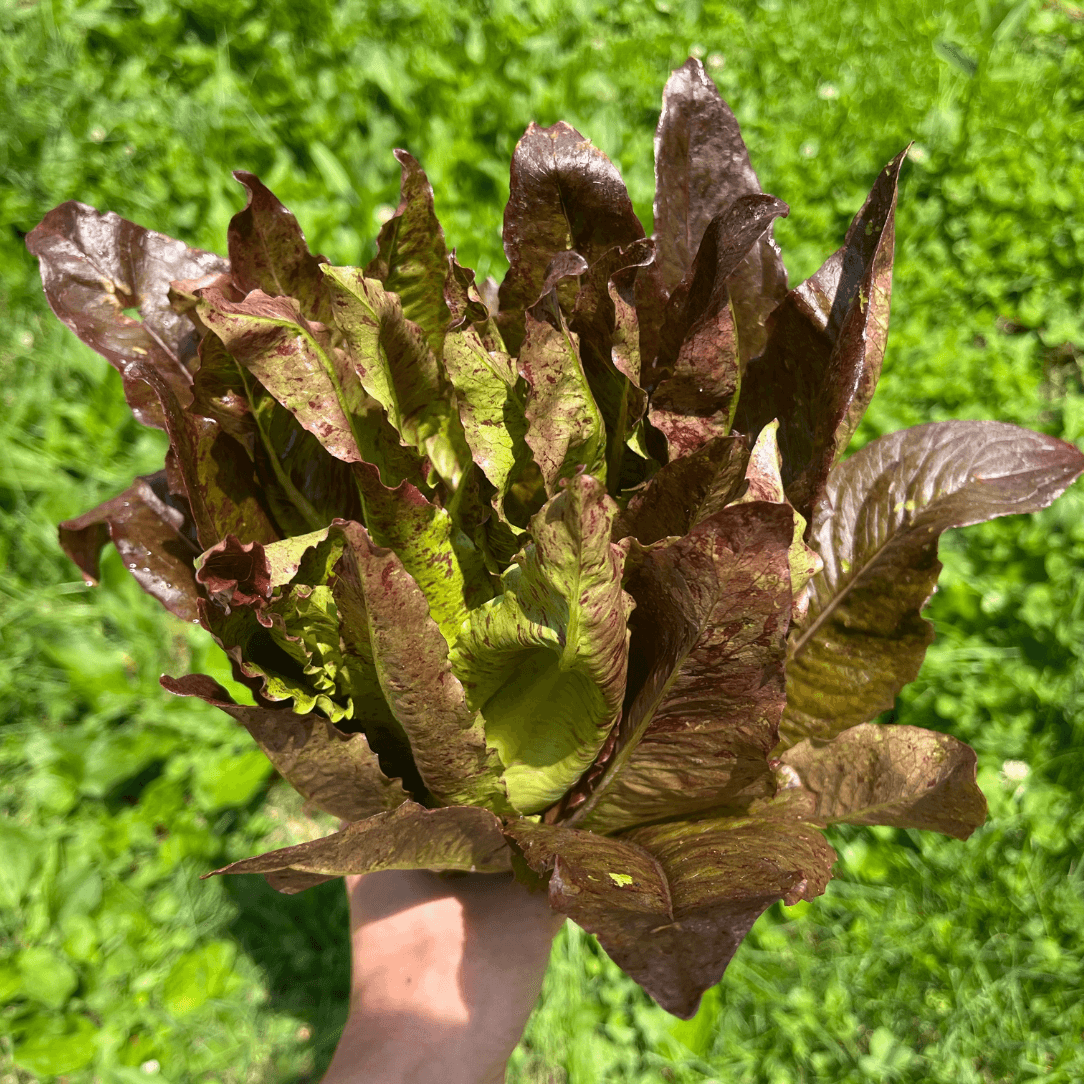

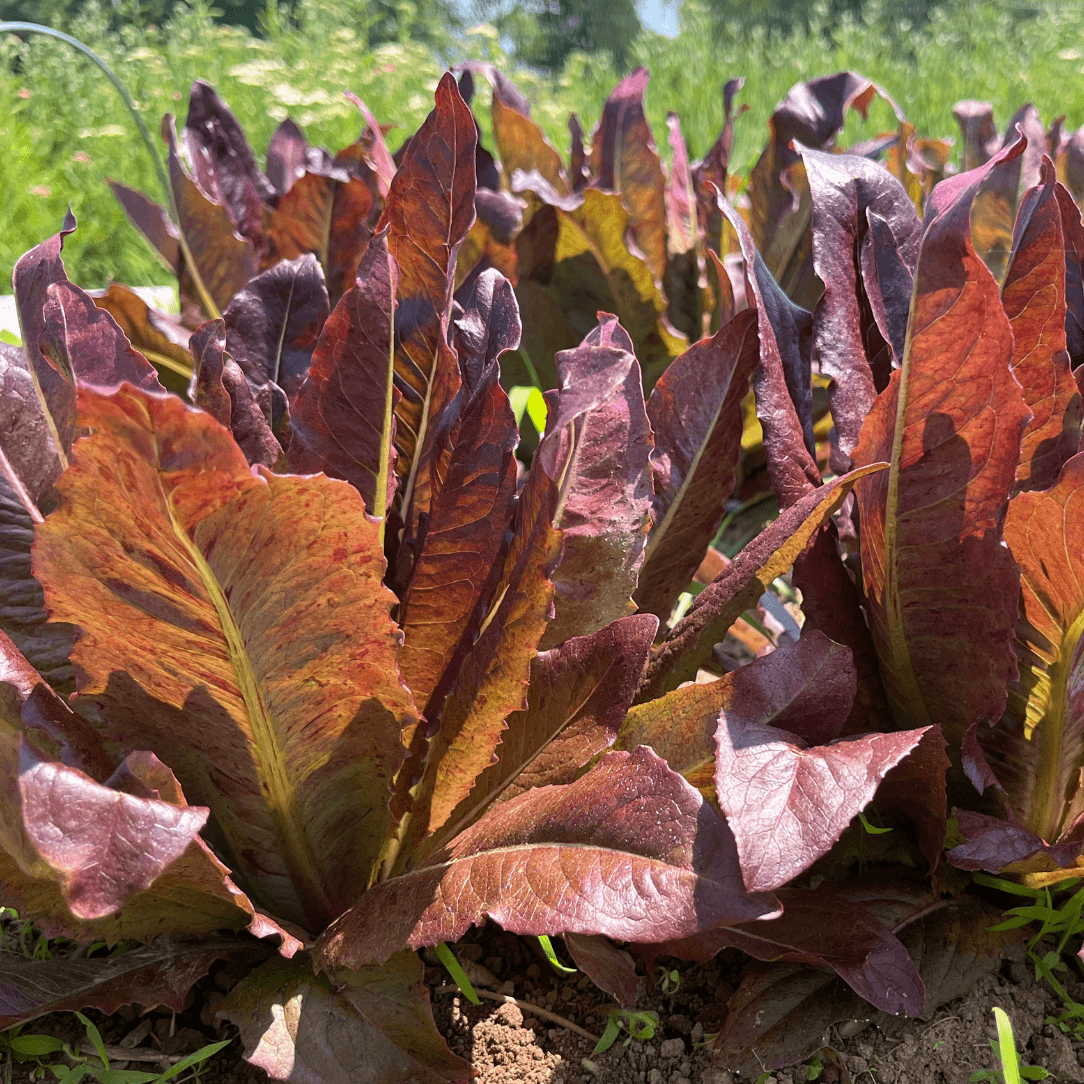

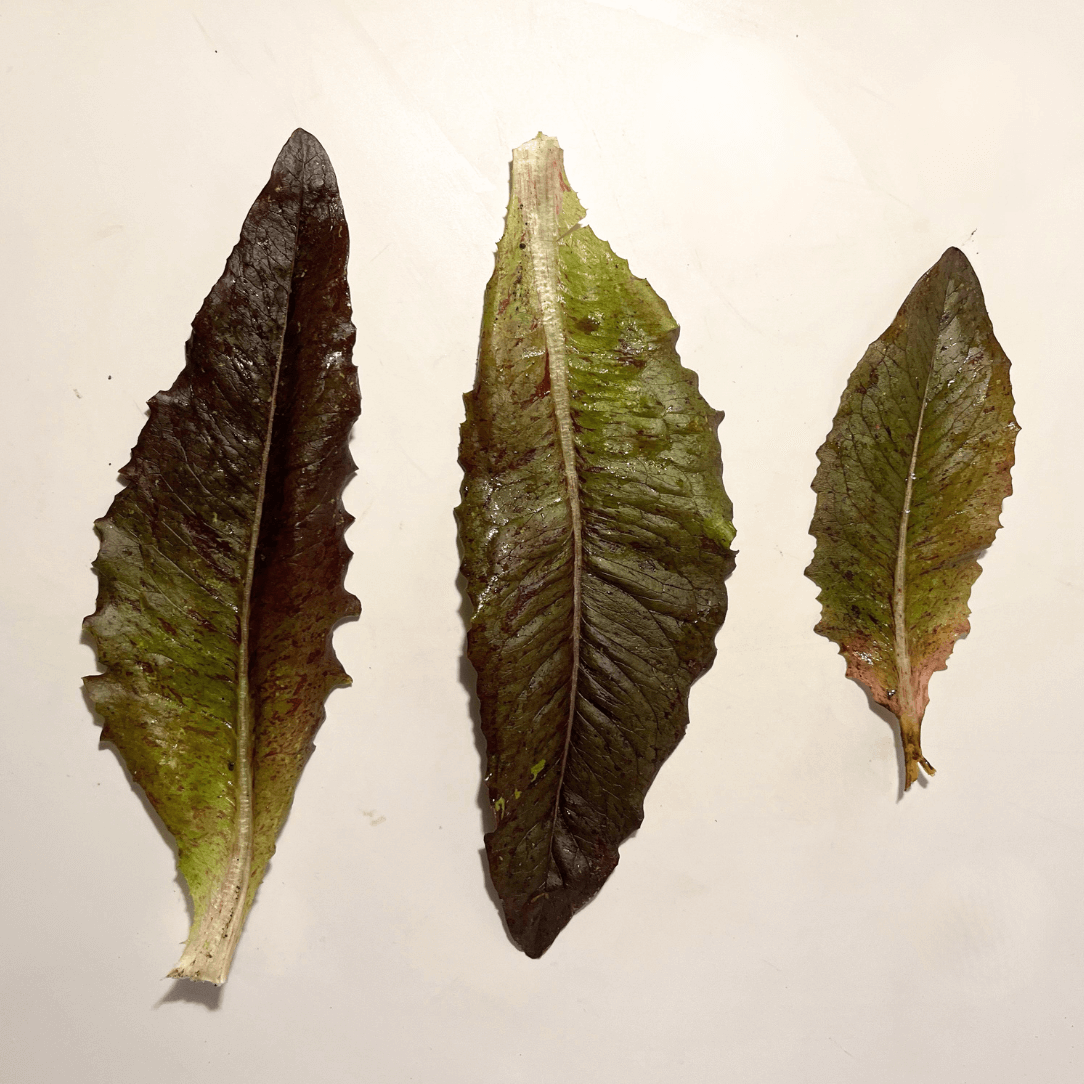

- Diversity within a crop: In some cases, you may be able to grow the same type of crop for both your hot and cold season varieties. Take lettuce: you can grow a cold-hardy variety like Prizehead at the beginning and end of the season, and a heat-tolerant one like Summertime in the middle. Or start Sugar Daddy and Tall Telephone snap peas simultaneously. By the time the shorter Sugar Daddy (30" at maturity) has finished producing, Tall Telephone (which grows up to 6') will be putting out plenty of peas.

- Diversity across crops: The naturally staggered life cycle of different crops can help you make the most of your space. For instance, you can plant peas in early spring, and when your last frost has passed and it's time to plant cucumbers, you can place them near the same trellis. When the peas have done their thing, snip them at ground level, remove the vines and leave the nitrogen-fixing roots, and use the trellis for your cukes. For flowers, choose a range of colors, textures, and heights (and be sure the taller ones don't block or shade out the shorter ones). Choose flowers for cutting, for drying, and for pollinating.

- Pollination: At any time of the growing season there are different plants that need pollination—and different pollinators that need plants. Aim to have something in bloom at each stage of the season.

- Annuals vs. perennials: Both are great! But intermingling them could cause problems: if your annual dill and perennial thyme are planted side by side, you'll risk damaging the thyme when you rip out annuals that have died back. If you're planning on tilling in spent crops (a great idea for soil health), make sure you don't have any perennial flowers or herbs planted there.

- Rotation: Crop rotation isn't just for farms. Home gardeners often don't realize that growing squash in one corner of your garden may mean that there are squash bore eggs and larvae in the soil that are very much hoping you'll plant squash there again. Mixing up where you grow things in succession, and from year to year, can help keep your plants safe.

- Avoid bare soil: How often in nature do you see exposed dirt? Maybe in a desert, but we're guessing that isn't your gardening goal. Keeping soil exposed can mean the loss of organic matter and other nutrients, and can encourage erosion. Bare soil is dead soil! Combat these issues by keeping a constant rotation of crops and succession sowing. If you run out of things to plant, use a cover crop to protect the soil, add organic matter, and maybe even fix nitrogen. During the season, crimson clover can also be used to line paths. For a home gardener, however, it's important to make sure you have the proper timing and equipment to deal with any cover crops you plant. If they're intermingled with your crops and allowed to set seed, you could be struggling with regrowth of that seed for seasons to come. Buckwheat is an attractive and fast-growing option for home gardeners, as are oats and peas, and both will winter kill to be easily tilled in.

- Grow what you like: It may seem obvious, but one of the most exciting parts of gardening is the joy of growing all your favorites in your own soil. Make your own bouquet of your preferred flowers. Plant the ingredients to your favorite recipes. Everything will look, smell, and taste even better for being homegrown!

LIVING IN THE MOMENT

So you've outlined your garden from now through fall—fantastic! You can bask in that sweet sense of organization and look forward to everything you've planned. Now that you've gazed into past, present, and future, let's take a breath and focus on the now—that is, which plants are growing together at the same time. Introducing biodiversity into your garden and growing many different things together allows the opportunity for different plants to develop symbioses with each other. This idea of planting different crops in close proximity for symbiotic benefits is often referred to as companion planting, and it can take a variety of forms. Consider these ideas:

- Variety selection: Choose varieties that will thrive in your region and your particular garden space. If you have a small garden, opt for dwarf tomatoes like Mandurang Moon and Summer Sunrise, and bush-habit squash like Table Queen Acorn Squash, or try Mexican Sour Gherkin for a smaller take on a cucumber.

- Variety quantity: There's a balance to be struck here. To have a thriving, diverse, open-pollinated garden means branching out in the number of varieties you plant. At the same time, it's important not to bite off more than you can chew. For the average home gardener, 3 individual tomato plants should be plenty; any more than that and you risk too much upkeep, space, and surplus fruit. But instead of growing 3 of your favorite red slicer, try a beautiful heirloom like Cherokee Purple, a paste tomato like San Marzano to get you through the winter, and a cherry like Honey Drop to snack on while you work.

- Size differences: Use the natural growth habits of your plants to your advantage. Tomatoes and basil are a common companion planting pair, not only because they taste great together, but because the shorter basil grows comfortably underneath the taller heat-loving tomato plants. Remember the example of the two snap peas from before? You can grow the Sugar Daddy under the Tall Telephone to save space. One of the most elegant examples of companion planting is the Three Sisters. Traditionally, Native Americans would plant corn, beans, and winter squash together. The corn acts as a trellis for the beans, which fix nitrogen and enrich the soil, while the squash vines sprawl beneath them and keep weeds at bay.

- Pest management: Protect your plants with...other plants! Herbs like thyme and mint are disagreeable to animals; catnip discourages flea beetles; trailing nasturtiums prevent cucumber beetles and squash bugs; the strong scent of marigolds deters pests—and their roots produce a compound that stays in the soil and acts against nematodes! It's worth mentioning, though, that for organic gardeners, nothing is as effective against pests as row cover.

- Bed ends: Include some flowers in your vegetable garden by planting them at the ends of your rows. It's a great way to add beauty, attract pollinators, and—if you're using some of the varieties previously mentioned—keep pests away.

BIODIVERSITY IN BRIEF

That grocery store produce can be cheap and convenient and, in many cases, necessary. But it can also put us in a box in regards to the amazing variation that exists in seeds. Over a relatively short period of time, we've lost an impressive number of varieties in favor of a handful of supermarket-ready monocultures, the seeds of which are often unavailable to the public. The Cavendish banana is a particularly glaring example of the detriments of biodiversity loss: they have a monopoly on nearly all bananas sold worldwide and the trees, which are all genetically identical, are now at great risk of succumbing to disease. Unless gardeners sow the seeds of seed sovereignty, and keep rare seeds alive in their gardens, the pool will narrow even more. A diverse garden means many things: it means more fun and flavor for gardeners, but it also means creating habitats, preserving genes, and expanding our ideas of what's possible.